Evidence Score: B

Score: 17/20 85%

Date discovered: 5/5

Understand of ancient languages began to increase during the 19th and twentieth centuries. During the 1970’s Hugh Nibley began to hypothesize about the entomology of the word.

The present theory began to be developed during the 1980’s by Steven Ricks and other scholars.

During Joseph Smiths lifetime and since the word Irreantum has been mocked relentlessly, indicating that plausible entomological roots with the proper mean directly challenges the understanding of 1829.

Biblical support: N/A

Archeological Support: 4/5

Each of the word parts however are common and found in many ancient writings, however, because the complete word “Irreantum” remains unattested in ancient writings some speculation to determine its entomology is required.

An ancient village was named using the root RWY

It appears that Nephi and his family may have themselves coined the word based on their understanding of local languages, for this reason it should not be expected that an archeological attestation of this word will be discovered

Scholarly Collaboration: 3/5

Correlation to text: 5/5

See all sources regarding Irreantum

As Nephi and his family arrived in their coastal oasis on the Arabian Sea, Nephi recalls “And we beheld the sea, which we called Irreantum, which, being interpreted, is many waters.” (1 Nephi 17:5)

Many critics have seen the word “Irreantum” and its translation as ridiculous. In 1838, Origen Bacholer mocked the idea, writing “Let us have the proof, Irreantum signifies a complete ass, nearer than anything else”.1

Such arrogance is not uncommon among critics of the church and the Book of Mormon. But, as Hugh Nibley so simply stated, “time vindicates the prophets”, and we now understand ancient languages far better than we did in 1829.

The provision of a “gloss” or interlinear translation, or the word “irreantum” provides us with a unique opportunity. While many transliterated words found within the Book of Mormon need only to demonstrate ancient linguistic roots. In the case of “irreantum” those roots must also match the given translation of “many waters”. Instances such as this occur six times within the book of Mormon. If Joseph Smith, or anyone in the early 19th century had written the Book of Mormon, they would have been careful to avoid such instances, which, as our understanding of ancient languages grows, allows us to more completely test the text against an ancient setting.

Because Nephi felt the need to provide an interpretation, we can assume that the word was not the language he was writing in or expected his readers to be familiar with, yet it would be a language with which Nephi himself was familiar.

The most immediately obvious language options would be those of the south Arabian peninsula, where Nephi and his family had recently spent 8 years traveling. Undoubtedly, Nephi would have gained some level of familiarity with those languages and there may have even been a desire to name to sea using the local language.

Using these ancient south semitic languages there certainly proves to be some validity not only to the word “irreantum” itself but also to it’s translation.

The prefix of this enigmatic word is “irre” which is not phonetically distant from the semitic root “RWY” which refers to water.

In modern Arabic روى, RWY, pronounced alone as “rawa” means water, or to quench thirst, or drink one’s fill

In ancient Sabian, RyhtWY means to ‘provide a water-supply’, RWYm refers to a water tank or a cistern. In Ge’ez, yet another ancient Semitic language RaWaYa means ‘to drink one’s fill, be watered, irrigated”2

Perhaps the best match however, is found in South Semitic, which was spoken in southern Arabia, Yemen and Oman, the very same region in which Nephi and his family had traveled and discovered the land bountiful. It is in this language that RWY means “abundant water” consistent with Nephi’s definition of “many waters”.

The reference of “RWY” often referring specifically to irrigation as well as water is not insignificant. The modern name of the location fitting Nephi’s description of Bountiful is Khor Kharfot. Kharfot has multiple meanings, but one of those meanings is “the monsoon rains have brought abundance to this place”3 referencing the massive rainstorms which form in the Arabian Sea and irrigate the coast. It is this irrigation that allows the growth of the many fruits and resources described by Nephi which can still be found growing wild in the area today.

A few hundred miles northeast along the coast of the Arabian Sea, is an archeological site which has been given the name “RWY-1” which they pronounce “Ruways 1”4, using the very same root as the Lehite name of the Arabian sea. This name was likely given because of the very same oceanic monsoons which frequent the coast, irrigating its shores.

Already the root has proven to have the appropriate linguistic origin and translation, however, the rest of the word cannot be ignored.

The suffix also bears semitic roots, in south Semitic, “tmm” “tm” or “tum” signifies completion, or fulfillment.5

The affix of “an” is common in semitic languages and serves simply to connect the two word parts.6 The transliteration of “an” is also particularly appropriate for south semitic, if this were a Hebrew word for example, it likely would transliterated as “on”.

Combining the word parts with their south semitic translations we arrive at a literal translation of “abundant waters of completeness” or more literally, and in line with Nephi’s gloss, “fully abundant waters” or “abundant waters”7

It is easy to imagine Nephi and his family, after spending eight years in Arabias empty quarter, walking along a wadi as it burst into a coastal oasis, bordered by the seemingly endless blue waters of the Arabian Sea. They would have recognized that it was the ocean which provided the water which irritated the coast and allowed the formation of the place they appropriately called Bountiful.

While the name “irreantum” may not be attested today in any Semitic language, and it may not even perfectly follow the rules of those languages. Its roots are undeniably Semitic, appropriate to the time and region. It is important to remember that this was a newer language to the family of Lehi, and while they may not have understood all the nuance of the languages they encountered on their journey, it appears they named the sea in the language of the area. Nephi specifies that “we called [the sea] Irreantum” (1 Nephi 17:5) and chapters 17 and 18 certainly read as though they were alone in the area, meaning the name would not continue in the region after their departure.

Of this much we can be certain, Irreantum is a word with strong Semitic roots, and Nephi’s interpretation is fitting.

Had Joseph, or any of his contemporaries written the Book of Mormon, it is unlikely, if not impossible, that a word, unknown prior to 1829, a word that critics would claim “signifies a complete ass”, would not only have root in the area where the word claims to originate, but that the translation of those roots would match the interpretation given by the text.

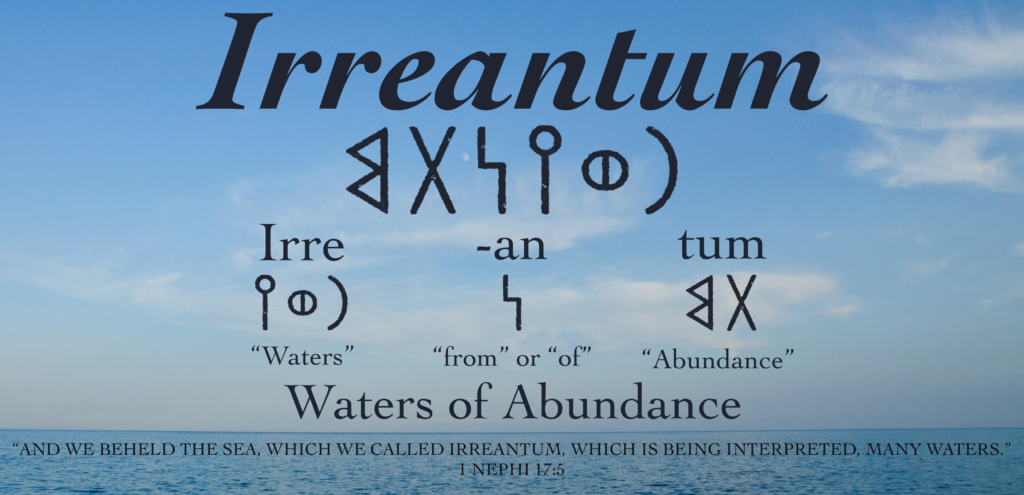

Authors note: The featured graphic uses Musnad script. It is very likely that the Lehite party encountered this type of script during their travels. And may have been the type of script they became most familiar with and associated with the regional language, which likely inspired the name “Irreantum”. Notably, The NHM alters found at Nahom of the same era as well as the funerary text bearing the name Ishmael, feature inscriptions in Musnad script.

- Bacheler, Origen. Mormonism Exposed, Internally and Externally. New York: O. Bacheler, 1838. pp 14

- Militarev, Alexander. “A Complete Etymology-Based Hundred Wordlist of Semitic Updated: Items 75–100.” Journal of Language Relationship 11 (2014): 159–185. Moscow: Institute of Eastern Cultures and Antiquity, RSUH. pp 178

- Warren P. Aston, “Across Arabia with Lehi and Sariah: ‘Truth Shall Spring out of the Earth’,” JBMS 15/2 (2006):8–25, 110, online at https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/

- Berger, jean-Francois & Guilbert‐Berger, R. & Marrast, Anaïs & Munoz, Olivia & Guy, Hervé & Barra, Adrien & López-Sáez, José Antonio & Pérez-Díaz, Sebastián & Mashkour, Marjan & Debue, K. & Lefèvre, Christine & Gosselin, M. & Mougne, Caroline & Bruniaux, Guillaume & Thorin, Stéphanie & Nisbet, Renato & Oberlin, C. & Mercier, N. & Richard, Maïlys & Béarez, Philippe. (2019). First contribution of the excavation and chronostratigraphic study of the Ruways 1 Neolithic shell midden (Oman) in terms of Neolithisation, palaeoeconomy, social‐environmental interactions and site formation processes. Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy. 31. 32-49. 10.1111/aae.12144. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/337490519_First_contribution_of_the_excavation_and_chronostratigraphic_study_of_the_Ruways_1_Neolithic_shell_midden_Oman_in_terms_of_Neolithisation_palaeoeconomy_social-environmental_interactions_and_site_forma

- Hoskisson, Paul Y., Brian M. Hauglid, and John Gee. “What’s in a Name? Irreantum.” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies11, no. 1 (2002): 90-93, 114-15.

- Jonathan Owens. “The Historical Linguistics of the Intrusive *-n in Arabic and West Semitic.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 133, no. 2 (2013): 217–48. https://doi.org/10.7817/jameroriesoci.133.2.0217

- Hoskisson, Paul Y.; Hauglid, Brian M.; and Gee, John (2002) “What’s in a Name? Irreantum,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 11 : No. 1 , Article 15.